The Pork Tour Day 5: Madisonville, Tennessee

I have been to the sine-qua-non of smoky-salty pork, and it is within a two-day drive of my house. Ham-el-lujah! Forty-eight hours after my visit with Allan Benton of Benton’s Smoky Mountain Country Hams, my hair, my favorite driving skirt (one needs room to spread on a trip like this), my car, Stella---all still smell like smoke. I don’t care. There are still artisans in this country who put their money where their morals are, without concern for a bottom line, and one of the best is holding court in a small building by the side of Highway 411, about an hour south-west of Knoxville, Tennessee. When I walk in, Allan is leaned up against a large cold-case chatting with a large baseball-hatted man who is draped on a bench opposite. Since I’ve called ahead, first about a month ago, and then again ten minutes ago,

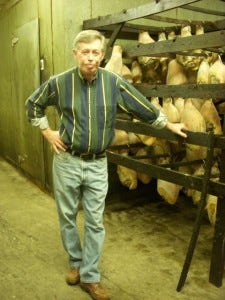

Allan is waiting for me and will devote almost an hour of his precious ham-time to showing me around what is, in the scheme of the ham world, a small operation. Every careful step of the sublime alchemy that transforms pig into smoky-cured ham and bacon takes place in this unassuming, medium-sized building--plus, of course, the smokehouse out the back. First, Allan introduces me to his friend, Eddie Griffith, who quickly tells me he’s a “loafer.” “Hanging around waiting for some scraps?” I ask. This gets me a big laugh and they both agree that I’ve got Eddie’s number right off. Immediately, we start talking about ramps. Ramps and ham are one of those luminous partnerships that deserve the same sort of reverent attention as spring moonlight and young love. “Everybody’s taken the ramps from the side of the road already, right now you got to go way up in the mountains to find any. In another three-four weeks, there’ll be a lot more down here,” says Eddie. I ask him how he prepares them. “In eggs, in salad, in a pan, we eat ‘em every different way,” he replies, but I do get him to admit that his very favorite is to fry up some nice fatty side meat, then add a few potatoes to sizzle in the grease, and throw in the ramps at the end just so they wilt. “If you don’t like that, you don’t like to eat.”

(Later, Allan tells me Eddie is the hands-down best cook he’s ever known. His extended family raise all their own meat and vegetables, render all their lard, make sausage and head cheese, and dry the fruit for fried pies and stack-cakes. More than anyone he knows of in this region of Appalachia, they are keeping the old foodways alive. Eddie’s wife, he says, makes “fried pies you could die for”.) For me, visiting the ham room is like seeing the first pale and hopeful shoots of my chard come up in May---full of pregnant, organic promise. The hams are rubbed with a salt-cure twice, the sides of bacon only once. After a month (10 days for the bacon), the racks go out back to the smoker. The “family cure ham” is rubbed with brown sugar, and Allan allows as he sometimes forgets to add the USDA-proscribed nitrites to this particular ham. Then comes the aging process. The oldest hams here will be 24 months old on the 7th of April. Ninety-five percent of the oldest hams go to restaurants, and almost all of them go out boned and sliced. I must have evinced a gut shock at this statement, because Allan hurried to reassure me that he sends the bones along, too.

Back in 1947, a dairy farmer named Albert Hicks started feeding the leftover whey to his pigs. The pigs thrived; later, so did those who ate the resulting ham and bacon. Hicks and his wife hosted a visitor from New York for a couple of days, and when he left, the man inquired about the provenance of the meat he’d been served for breakfast. Could he buy possible some? Hicks allowed that such a transaction was possible, but when his visitor mentioned a hundred hams, protested that they only cured a couple of hams a year. Eventually, Albert agreed to buy in pigs from local farms and cure them his particular way, and that’s how the business was born. Cut to about twenty years later: young Allan was chewing over his career options: law school was high on the list. Then he heard that Hicks—whose operation had never been approved by the health department--had closed down, and that was, for Allan, simply that. After bringing in just a little bit of modern innovation, Allan started the business back up with the health department’s blessing. “But Albert taught me things you can’t learn in any textbook,” he says. Now, Benton’s produces 14,000 hams a year; this may sound like a big operation, but the large ham producers make close to a million. Allan doesn’t see the need to make more. “My goal is to make exquisite ham, not money,” he tells me.

Allan had never put much thought into the way pigs were raised; he just bought the pigs and made hams the way Albert Hicks had half a century earlier. Then, he went to NY to sit on a panel with Peter Kaminsky, author of the profound and seminal work “Pig Perfect.” The experience literally changed Allan’s whole philosophy. He walked out of there resolved---not to change the way he makes ham and bacon, but to change the pigs his products come from. Now, he tries to find farmers that are raising hogs organically, with no antibiotics in the feed. “We pay through the nose for it, but if you’re trying to make a good product, this is what you have to do.” He gets as many hogs as possible from Heritage Foods brokers, a co-op of about 450 farmers. Other sources include Henry Fudge in Birmingham, and a farmer 150 miles down the road, Wes Swansea. But the availability isn’t quite good enough to cover all his needs, so he still uses some feed-lot pigs. But, when it comes to feed lots—an exceedingly sore subject among those of us who love not just pork but the pig itself, Premium Standard Farm is as good as they get. It’s a relatively small farm, and they do everything by hand.

Such passionate devotion to the details, large and small, does not go unnoticed. Benton’s hams have developed a devoted following. As we walk toward the door and I prepare to enter the low-ham-zone of the outer world, I spot an open carton of bony shank ends on the floor. They seem almost forgotten in the seemingly haphazard (but, actually carefully proscribed) progression of hog to ham. The shanks are mottled, salt-crazed, not immediately the most attractive items in the room, but to this pork-aficionado, they are silently screaming flavor.

“What happens with those,” I ask, trying not to look too vulture-like. “They go to someplace called Momofuku,” Allan responds, immediately dashing my plans to spirit just a few away. Oh well, David Chang clearly has nefarious plans for these unlikely pork parts. To taste their secrets, I guess I’ll have to visit his lair. “If money was all that motivated me, I’d have found an easier way to make a living,” Allan told me, as I left with a bagful of vacuum-packed nirvana. We who are the beneficiaries of Allan’s passion and pride must stand up and vote with our bellies. Not just for Benton’s ham, bacon, and domestic prosciutto, but for farming and animal husbandry standards that will make his pigs happy, healthy, and delicious. In that order.