The Bolo-Tie Syndrome

Marfa to Alpine. And back. 52 miles. You know what this is, right? You don’t? OK, you are in Santa Fe. You’ve just come back from Ten Thousand Waves, where you came to love the smooth, warm stones so much that you’d really like to propose marriage to them. You sat in a wooden tub outside, gazing at the sloping golden hills, and watched them slowly reach electric clarity in the sharp light of the setting winter sun. Now you are having a shot of tequila with a side of sangrita in the square, and all the calculatedly rough-and-tumble locals who amble by in their perfectly worn jeans are wearing bolo ties. You have some pretty perfect jeans, too, and your boots are scuffed up enough that you don’t look like some drugstore cowboy who only ever had a charley-horse. Clearly, it’s time for a your very own bolo tie. You amble down a side street and find a cute little adobe shop where a post city-slicker refugee with a 12 o’clock shadow and corkscrew curls is working shiny Mexican silver with turquoise and coral into wild and wonderful shapes. You shell out enough cash to burn a wet mule, and now you’ve got your very own spit-polished bolo tie. It slides up like butter and all of a sudden you just feel right with the world.

When you get back to (insert name of hometown here), your bolo tie suddenly seems like a rash purchase. It sits, tarnishing, in the top drawer of the bureau next to the cap gun from your 12-year-old Halloween cowboy outfit and all the pretty journals you’ve bought and never written more than a page in, for fifteen years. We all go through some version of this, whether it’s the almost non-existent thong bikini from Rio de Janeiro or the huge tagine from Morocco (sorry, using it twice a decade doesn’t justify the purchasing and lugging involved).

On Saturday, I ambled over to Alpine to hear some cowboy poetry. There are Cowboy Poetry Gatherings all over the west, but this is the most famous. It’s where Baxter Black and plenty of other well-known scribes got their starts. During the writing of Cowboy Cocktails, I read lots of cowboy poetry to get myself in the right mood. (Yeees, the mood to write cocktail head-notes; I didn’t have a lot of other work at the time, and so threw myself into the project like it was a doctoral thesis.) When I decided to come to Marfa for a month and work on The Book, I didn’t even realize that, fortuitously, the Gathering would fall almost exactly halfway through my stay.

People who aren't from the west laugh when they think about cowboys writing and reading poetry, and some of it is definitely funny. But more of it is introspective. Cowboys, real and imagined, spend a lot of time alone, or almost alone, and they do a lot of waiting. This gives them time to ponder. They wait for rain (this is a recurrent theme in the verses), wait for cattle to finish eating, wait for the sun to come up, wait for it to go down. Along the way a cowboy learns a lot about nature, maybe not human nature, since it’s often a solitary existence, but about Mother Nature. I watched a classroom-ful of people at Sul Ross University---men and women, cowboy-hatted and baseball-capped—closely follow every word of a cowboy’s song in which he wondered if it would ever rain again. They nodded knowingly, as one, when the following verse came along: “I wondered if that mighta been a cloud I saw, somewheres ‘bout noon yesterday.” These people know the land, and they know its sweetness and its cruelty in equal measure. They love their animals with a passion that belies the fact that cattle are raised to be eaten and dogs are there to work hard for their supper. Horses, now there’s the true love of the man or woman who lives on the land. Horses are more like people than they’re like cows or dogs; you don’t eat them, and you sure don’t order them around. People come from all over the west and the world to hear these poets and songwriters because their words resonate right down to the bone.

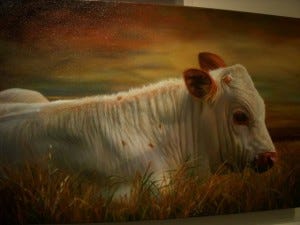

Next door in the Sul Ross museum, there was a for-sale exhibit called “Trappings of Texas.” Contemporary silver and leather-workers offered spurs and saddles that were so beautiful that I found my hand wandering towards my credit card, even though I haven’t ridden in years (hey - I WAS a damned good rider, back in the day). Bolo tie, I muttered to myself. The paintings, of which only two are here, are mystical and serene and capture the tough beauty of this land in a far quieter way than the poets do. I am disturbed, however, by the lack of discernable eyes in this very lovely heifer. Is she making a judgment on those who admire her beauty and yet turn her into porterhouse? Was it too difficult for the artist to imagine what those eyes would convey? Ranching has never been pretty, and it’s certainly not an easy business to be in, what with mother nature is at your throat every step of the way. There’s no room for sentimentality on a ranch. (My mother spent much of her childhood on the huge Hollister Ranch north of Santa Barbara, long before it was split up into luxe mini-ranches, and remembers a cowhand beating a recalcitrant horse to death right in front of all the ranch children.) But spending just a day among the poets and artists of the West leaves me in no doubt at all: whether there’s elbow-room for sentiment or not, it’s a big part of these big-hearted Texan’s lives.