Bereavement Soup

1.30.09 Mar Vista, CA There is something about death and illness that triggers a desire for soup. To cook it, and to eat it. What happened in Mar Vista two days ago was so awful that the only tolerable emotion my girlfriend, chef Jill Davie, could identify was an auto-drive soup imperative. I was riveted, the helpless spectator as an extraordinary transformation took place, from hysterical gladness to violent disbelief to tears and, much later, to a rich—if ephemeral--condolence.

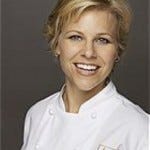

I arrived at 4 pm; after not having seen Jill for six months, I would be staying at Villa Jilla for three nights. She was on a high: the restaurant she’d been wanting to open for a year and a half, since she left her position as chef at Santa Monica’s Josie, might become a reality. She and I had tried to open an artisanal pizza joint together last year. But after months of mutual blood, sweat, tears, and money, it had proved undoable. She received a text from a friend: A private plane had crashed at Santa Monica airport (about half a mile from both her current and childhood homes); “Was your dad flying today?”

No, her dad wasn’t flying today. Every few years, there is a plane crash at this throwback of a charming, urban airport; I lived within a mile of it for thirteen years and could recall two. Most of the planes are so light that fatalities and serious injury are rare. She joked to me: “Maybe we can see the smoke if we go outside.” Later, we would recall this with horror. At 5pm, we watched the local news. There was a picture of the plane: it was sleek and bright red---an experimental Italian aircraft---motionless in a pool of fire-retardant foam. It looked like a broken toy in a bathtub. The two people on board had died, we now learned. The news continued, with more bad and sad Los Angeles news: a high-speed, wrong-way driver on I-10 had killed a police officer, the father of two. A recently-fired man had shot his wife and five impossibly beautiful chocolate children. A rapist had struck again. My small-town self leaked quiet tears as I watched. Then another text came in, from a different friend: “Is it true? Was it Paolo?” I watched her face over the next fifteen minutes, as the texts rolled back and forth and the truth she tried vainly to push away, like a tsunami, became inescapable. Her disbelief turned to breathless, face-squinching nausea, like a participant in that carnival ride where the huge, people-lined barrel spins so fast that everyone is centrifugally glued to the edges, and then the floor drops out. I did not know the man who had just died, Paolo, but he had an eleven-year-old daughter and had just moved in with his girlfriend of four years. They were happy. He was a successful club owner. Everyone had plans.

My immediate urge was to run over to Whole Foods and secure the ingredients for a chicken soup. (I did the same thing recently, when one of our closest friends back east was rushed to the hospital with a heart “incident.”) One thing I know how to do is cook, and in the absence of understandable answers, cooking is perhaps the least unbearable of the options that come to mind. But in the cooking department, I can’t hold a candle to chef Jill; my thought of chicken soup was to her inspiration as a poppy to a parrot tulip. She opened the refrigerator. In the current absence of regular employment (not counting her show on Fine Living, and acting as a spokesperson for Sunkist), Jill has dabbled in catering. I have always found the contents of her refrigerator to be blissfully schizophrenic, often mysterious, and sometimes frightening. Now it all came out: carrots, many pounds of celery, a plethora of small, cheese-and-tequila-filled pork sausages, jumbled falafel, peeled garlic, last week’s romesco. A butternut squash appeared. I peeled and chopped and harbored secret doubts that such an odd amalgam could become ambrosial. I hadn’t reckoned with the visceral instincts of a CIA-trained chef who has managed some of West Los Angeles’s most respected restaurant kitchens. At 11:00 pm I went to bed, having become tired, and extraneous to Jill’s fierce attention to the bereavement soup. I heard dim sounds of cooking in the dark house, rested my feet on the reassuringly plump firmness of my black and white dog, and missed the presence C, now far away from me in New York, in a cold, cold house. Why had I chosen two months of separation over togetherness in the chill of a northeast winter, when life held such cruel possibilities?

In the morning, a large pot sat wordlessly over the barest whisper of heat. The house was filled with a haunting, consoling aroma that didn’t know if it was curry, pork, butternut squash, or something eloquently its own self. Later, when the heartsick best friend---who had driven up from San Diego---warmed up the soup Jill had made for him, his tears added salt to the elusive bouquet. The soup was insignificant in the larger scheme of grief. But in its small, secret way the soup had brought a brief return of balance to hearts adrift in a heartless sea.